A step forward?

The year-end figures for the provider sector in England could be likened to the curate’s egg – good in parts. Or perhaps that should be improving in parts. The overall deficit is down, providers treated even more patients than the year before and productivity has improved. But the deficit was bigger than planned and there are still significant numbers of providers in the red.

The year-end figures for the provider sector in England could be likened to the curate’s egg – good in parts. Or perhaps that should be improving in parts. The overall deficit is down, providers treated even more patients than the year before and productivity has improved. But the deficit was bigger than planned and there are still significant numbers of providers in the red.

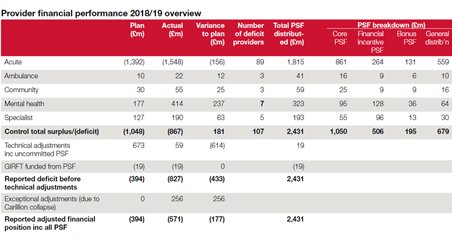

At the end of the 2018/19 financial year, the provider sector recorded a net deficit of £571m – £395m better than 2017/18 and around £90m better than the year-end position forecast at Q3. NHS Improvement said the provider sector contributed to an overall balanced financial position across the NHS when the commissioning sector managed underspend was taken into account.

It promised a new financial regime that would move away from blanket control totals after 2019/20 and regional support to improve trust financial controls.

‘The NHS 1.1 million staff delivered care to more patients within national standards, improved quality, and stepped up efficiency to deliver one of the best financial performances in the last five years,’ said Ian Dalton, NHS Improvement’s chief executive. ‘The NHS long-term plan will build on this achievement by giving staff the support they need to secure the future sustainability of the NHS by managing the needs of an ageing and frail population.’

A good financial position at year-end was important as 2018/19 was a preparatory year for the advent of the new funding settlement and implementation of the long-term plan in 2019/20.

However, the final position was worse than any of the planned deficits set during the financial year. The planned deficit position was reset in-year – first at a £519m deficit, then £439m and finally settling on £394m.

The final position also includes the benefit of technical adjustments following the collapse of construction firm Carillion. Two private finance initiative hospitals being built by the firm were taken back onto the books as part-donated assets, benefiting the overall position by £256m.

And though more than £3bn of cost improvement programmes (CIPs) or efficiencies were delivered, this still fell short of the planned amount. There was also an imbalance in the delivery of recurrent and non-recurrent CIPs.

Providers’ underlying deficit at year-end was £5bn – up from £4.3bn – though this would reduce to £2.55bn if the Provider Sustainability Fund (PSF) is deployed.

Taxpayers, politicians, and some in the NHS, would argue that providers should be delivering better financial performance given the amounts of funding they have received – including £2.45bn in the PSF – at a time when other parts of the public sector remain starved of cash.Of course, the NHS is facing more demand than ever – A&E attendances in the 12 months to May were 4.2% higher than the preceding 12 months and there were 2.2% more completed elective pathways compared with 2017/18.

While activity growth increased productivity (which grew by 2.3%), it is also skewing the overall financial picture by, for example, affecting the delivery of cost improvement programmes, including savings on agency costs. There is also evidence that the growth in non-elective work is displacing elective income.

It was always going to be a slow march back to financial balance – the NHS long-term plan told us the provider sector should return to financial balance in 2020/21. By the end of the current year, the number of trusts reporting a deficit should have reduced by half, with no trusts in deficit by 2023/24.

The new financial regime, with its promised shift away from control totals, should lead to more transparency and accountability, as well as support to reach these ambitions.

But the more immediate targets – cutting the number of deficit trusts by half and achieving overall financial balance by 2020/21 – could prove testing. The 2018/19 figures show a number of trusts with relatively small deficits (around 20 of less than £5m when PSF is included), but the total number of trusts in deficit was 107 (it was 102 in 2017/18).

To meet the ambition set out in the long-term plan, at least 54 deficit trusts will need to generate a surplus this year, assuming no further trusts fall into deficit.

NHS Improvement said a small number of trusts ‘did not deliver acceptable financial performance’ in 2018/19. These trusts accounted for most of the sector’s financial problems. Excluding the PSF, 29 providers (12.6%) reported a variance from plan of more than £10m. These providers accounted for £569m (120%) of the sector variance from plan – again, excluding PSF.

Under-delivery of CIPs continues to be one of the biggest reasons for the variance. In 2018/19, £3.2bn of cost savings (3.6% of spend) were made – an almost identical number to the previous year. Providers had planned to make cost savings of almost £3.58bn (4.1% of spend).

All but £451m of the planned savings had been due to come from recurrent measures, but providers failed to achieve this. They delivered £2.2bn of recurrent savings, missing the target by £904m. Much of this shortfall was made up by non-recurrent measures – the sector delivered just over £1bn in non-recurrent savings.

Pay cost savings accounted for the largest under-delivery against plan. They were £322m (22.5%) behind plan, driven by the rise in non-elective activity and recruitment difficulties.

NHS Confederation policy director Nick Ville said: ’The reduction of £395m in trust deficits this quarter compared with the fourth quarter

of 2017/18 offers some hope, but this report rightly recognises that we are overly reliant on one-off savings.’

Trust figures show large variances in patient care income (£1.76bn surplus) and pay-related expenditure (£1.95bn deficit), driven largely by the new Agenda for Change settlement. Pay funding was not included in the plan as the deal was agreed during the year. The government provided an extra £783m during the year to cover the cost of pay rises, but NHS Improvement said the new deal had led to cost pressures for a small number of trusts. The overall impact of the pay awards was £832m, leaving a £49m shortfall.

Temporary staffing was another leading cause of overspending against plan on pay. The need for temporary staff can be seen in the vacancy numbers. At the end of 2018/19, 96,350 posts were vacant, a fall of around 2,400 whole-time equivalents (WTEs) compared with the end of 2017/18 – more than 39,000 in nursing.

The reduction in agency spending is one of trusts’ key CIPs. Since ceilings on agency spending were introduced in 2015/16, agency costs have steadily declined, ending 2018/19 at 4.4% of total pay costs. Trusts overshot their agency spending ceiling by £201m (9%) due to increases in the volume of staff and not because agency rates have increased, NHS Improvement said. Average prices per shift are 5.4% down on 2017/18, while shift volumes are up 5.3%.

While minimising agency spending, trusts have been able to get the staff they need by increasing bank spending. This was £666m (24%) over plan. NHS Improvement seems more sanguine about these costs, saying they are a financially more efficient way of dealing with activity pressures. ‘By controlling agency spending, the changes of the last three years have led to better workforce planning and improved value for money in this area of significant spend,’ it said.

Temporary staff needs are fuelled not only by vacancies, but also demand.

The huge demand for emergency care is well-known, with performance statistics providing a monthly reminder.

Trusts received more than plan from increased A&E activity – £81m (3.4%) over

plan at year-end. Non-elective income was £587m above plan, but costs were higher than planned due to increased activity. This increased income was offset by elective income being less than plan – by £191m (2%).

NHS Improvement said this was a continuance of the trend where emergency pressures displaced elective income – for example, because scheduled procedures have been cancelled due to beds being prioritised for emergency admissions. Non-elective income tends to be loss making.

King’s Fund chief analyst Siva Anandaciva said the NHS ‘was running to stay still’ in 2018/19. ‘The NHS is treating more people than ever, and is in the grip of a workforce crisis. The new funding deal for the NHS will not wash these endemic pressures away. Unless the government delivers on its promises to address staffing shortages and provide investment and reform for social care and preventative services, it is hard to see how NHS providers can get back into the black and meet waiting times standards.’

Despite the improvements, the provider sector in England faces a big challenge to return to financial balance in the coming years. Money and resources have been set aside to help, especially providers with the most entrenched financial problems. However, providers do not operate in a vacuum and will continue to be affected by issues such as rising demand and staff shortages. Action on these issues will decide whether 2018/19 marked a step forward.Related content

The Institute’s annual costing conference provides the NHS with the latest developments and guidance in NHS costing.

The value masterclass shares examples of organisations and systems that have pursued a value-driven approach and the results they have achieved.