Feature / The right tool

Does your organisation make good, value-based decisions? Are they made as quickly as stakeholders expect? How often are they implemented as intended? Are sufficient resources allocated to making and executing decisions?

Does your organisation make good, value-based decisions? Are they made as quickly as stakeholders expect? How often are they implemented as intended? Are sufficient resources allocated to making and executing decisions?

Future-Focused Finance (FFF) believes NHS bodies cannot answer these questions positively and has developed a toolkit that can help introduce value and structure to their decisions. And with NHS decision-making so hit and miss, there have been suggestions that the toolkit, or something like it, could be mandated.

The FFF toolkit has four stages (see box):

- What

- Who

- How

- When.

Value, which is defined as clinical outcomes plus patient experience and safety divided by costs, is a key element.

‘Best possible value’ action area lead Caroline Clarke says the value component of the toolkit sharpens the focus on the factors a trust wants to influence and improve.

‘We surveyed several hundred staff in the NHS and found that people weren’t clear about roles and responsibilities,’ she says. ‘They focused on very small aspects of making decisions, and there was an issue around when we say we are going to do something and then don’t do it.’

Consultancy Bain & Co advised FFF on the decision tool. ‘Bain talked to us about how we compared to the best companies that make good decisions. It’s no surprise that there is a clear correlation between return on investment and good decision-making and staff satisfaction and good decision-making.’

The complexity of NHS organisations means that decision-making frameworks are vital. Ms Clarke’s own trust, the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, acquired Barnet and Chase Farm Hospitals last year, in a process that took two years, 53 board-level meetings and 19 levels of approval.

‘We couldn’t work out who was in charge or where the money was,’ she recalls. ‘It can be really hard to make decisions in the NHS and that spurred me into getting involved in this programme.’

Liverpool Clinical Commissioning Group (LCCG) and Mid Cheshire NHS Foundation Trust have piloted the toolkit. LCCG became involved in the decision-making framework pilots as part of its backing for the wider FFF programme and to support the city-wide transformation programme, Healthy Liverpool.

CCG approach

CCG programme project accountant Matt Greene says the commissioner has an opportunity to invest in new ways of providing services, but it has to be sure it is getting the best value for its money.

Mr Greene says decision-making in a CCG is complex, involving lots of stakeholders and committees, and there’s also the potential for conflicts of interest. Using the toolkit and being transparent about the process can help deliver robust governance, he says.

He insists that the toolkit is not a replacement for the business case process, but it can be used before writing a business case to focus thinking, ensuring the CCG makes decisions that provide assurance and stability to future planning.

One recent Healthy Liverpool decision taken using the toolkit focused on a decision on lung cancer services, under its Healthy Lung project. The city has one of the worst lung cancer survival rates in Europe. The primary phase of the project would raise awareness of the disease and promote prevention in the wider community. In the second phase, low dose CT scans would be offered to those most at risk, to detect the cancer at an early stage.

The toolkit helped bring clarity to a complicated decision that in the past, had been delayed as a result of using traditional, consensus-driven methods. Such methods often lack clear accountability of roles, responsibilities and powers from stakeholders and committee members. The toolkit has enabled directive and participative decision-making, which, combined with an excellent project manager, has helped to move the decision forward, Mr Greene says.

With the help of Bain & Co, support organised as a result of LCCG successfully applying to be one of two FFF national best possible value pilot sites, the CCG organised a series of workshops with stakeholders. They included public health doctors, GPs and consultants, who had the opportunity to run through the toolkit with CCG staff.

‘If you can get everyone to work through the decisions, they leave with a complete picture of what’s got to happen and what their actions are, rather than with mixed messages,’ Mr Greene says.

What phase

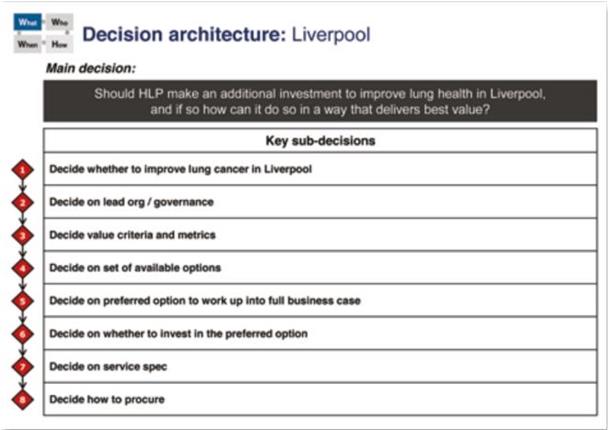

In the ‘what’ phase, the overall decision on whether to make additional investment in lung health in the city was split into eight sub-decisions, such as choosing metrics. Each workshop focused on a particular area of the toolkit and ‘minutes’ outlining the topics discussed, and agreements made, were written up and circulated before the next workshop. Taken together, these form a decision handbook.

In this phase, the project also examined the value components, outcomes (including clinical outcomes, patient experience and safety objectives) and resources (revenue and capital costs), including the metrics to measure these. This is captured in the value equation.

Mr Greene says this helps narrow down the objectives behind a proposed change – the desired outcomes and how to ensure services are improving, including what to measure.

‘During the decision-making process a list of options to move forward should be generated,’ he says. The option that offers the best trade off between the value equation components should be selected. It should be acknowledged that the toolkit does not conduct an option appraisal but capturing stakeholders’ opinions of what constitutes value will make this easier.’

Mid Cheshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust is using the toolkit in a longer-term decision. The trust has a partnership with University Hospital of North Midlands and is exploring how this could benefit both parties.

Mark Oldham, Mid Cheshire’s director of finance and strategic planning, explains: ‘They have a significant challenge around elective capacity and we have some spare capacity. We are exploring how we can help them deliver the 18 weeks referral to treatment standard and support our financial position through increasing the volume of patients going through our theatres.’

Traditionally, faced with this situation, a trust with spare capacity might jump straight to making a business case for patients coming from the other trust. However, the toolkit directs the trust to consider all the issues – for example, how many patients will be able or willing to travel, or what workforce issues must be taken into account – before working up a business case.

‘The process made us sit back and consider the options and identify what value means to us, so we come up with a more rounded decision. It prevents people diving into solution mode, only to realise halfway through the project that the workforce model or the estates planning doesn’t work with their solution,’ Mr Oldham says.

‘We have introduced the idea of value and how you quantify that. We spent a lot of time talking about value in terms of a financial contribution, but we also looked at clinical quality in terms of outcomes for patients and waiting times.

‘We used these to define value – why we were doing something and how we assess it against each of these value criteria. We were keen to ensure that what we were doing would not have any unintended consequences on the quality of services to patients.’

It’s a complex issue, with the Mid Cheshire trust believing that, initially, a partnership on elective work could mean 5,000 additional operations, worth £5m to £10m, each year. To address the issue, the trust created a multidisciplinary team that has boosted clinical engagement. Finance is playing a key role.

The project team produced a matrix of more than 100 options for providing the elective activity, paring this down to six possible solutions with a desktop review.

‘We are working through what the operational model would look like and then we will attach the finances to that so we can assess the value of each option,’ says Mr Oldham. A proposal is expected to go to the trust board at the end of next summer.

RAPID reaction

In the ‘who’ stage, the FFF toolkit directs the users to think about the roles different stakeholders will play. The RAPID model – recommend, agree, perform, input and decide – is used to clarify stakeholder roles in each sub-decision. Individuals or groups are assigned to each of the RAPID roles:

R Largely one person or group collects the information and develops a recommendation. In the Liverpool Healthy Lung project, often this was the local cancer programme group – but again this role can shift between an individual or group depending on the decision context.

A This group has influence, but does not make the final decision. They may be regulators or, in the case of the Healthy Lung project, Liverpool CCG finance team, which had A status in a sub-decision on whether to invest in the preferred option.

P This group are the performers – those who implement the action.

I There can be multiple inputters, such as providers, cancer network and patient organisations. They voice their opinion, though their views do not have to be reflected in the final decision

D Only one individual or group should make the final decision, though the identity of the decider can change depending on the sub-decision. In the Healthy Lung project, the finance, procurement and contracting committee had this role in the sub-decision on how to procure, but the CCG governing body and the Healthy Lung programme board were deciders on other sub-decisions.

Finance has a crucial role to play throughout the decision-making process. Its role often calls for input earlier in the decision-making process, but this can shift to agreement when a final decision involves committing funds must be made.

Mid Cheshire found the RAPID model useful. ‘It showed us who held what decision-making powers – that was enlightening,’

Mr Oldham says. ‘The clinical leader on the project often said they had been unclear in the past on what they could and couldn’t decide on, but in this the decision-makers are set out up front together with the opinions they need to consider.

‘There are often a lot of decisions taken by committee or by people passing decision-making around because they don’t want to make a difficult decision.’

Mr Oldham says that while the toolkit is useful, some organisations may wish to use their own project management structures to timetable and implement their decisions. ‘It’s useful for major strategic decisions, but if you are using it on a day-to-day basis, it is probably a bit unwieldy,’ he says.

As a pilot site, the Mid Cheshire trust received support from Bain & Co for the first seven weeks of the project. The company provided training on the use of the toolkit, facilitated workshops and did some activity modelling.

Mr Oldham believes that without this support, some organisations may find it difficult. FFF, however, is looking at a ‘lighter touch’ model, primarily for use on internal decisions and decisions where the value is lower.

He adds that the toolkit has prompted the Mid Cheshire trust to revisit its scheme of delegation and governance. ‘We realised a decision could have to go through a number of hoops – too many in some cases. Someone could pull together a business case, an executive may sign it off, but then it would go to the executive management board, which may take a different view, so it loops back again. One business case went through this process 15 times.’

Now, the trust has executive leads who can sign off business cases, which will then go directly to the trust board rather than the executive management board.

The toolkit offers the NHS a new way to make structured, value-based decisions. Indeed, the NHS England new care models team is using a version of the toolkit to evaluate the vanguard programmes.

The onus is now on the wider health service to adopt the toolkit and show they are using the right tool for the job.

|

Toolkit stages The toolkit has four stages in its decision roadmap. What: define the decision; frame the decision; define the value criteria and metrics; and split into sub-decisions. Who: for each sub-decision identify the stakeholders and clarify decision roles using the RAPID method How: install a structured decision approach, including meetings and committees but ensure there is closure on and commitment to the decision, as well as feedback loops. When: ensure there are clear timelines and milestones for each stage of the project. |

Related content

The Institute’s annual costing conference provides the NHS with the latest developments and guidance in NHS costing.

The value masterclass shares examples of organisations and systems that have pursued a value-driven approach and the results they have achieved.