Feature / A permanent solution

Controls on agency spending have saved nearly £300m between October 2015 and the end of February, and the trend of rising agency costs has been reversed, NHS Improvement has claimed. But more benefits could be realised and finance directors need to take a more central role.

These are the key messages from an assessment by the provider improvement body and regulator of the impact of the controls and caps introduced to reduce agency spend, which is making a significant contribution to wider provider deficits.

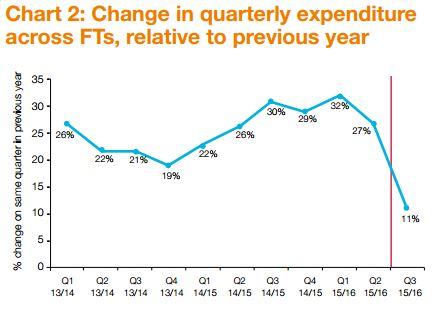

The backdrop to the new controls was a rapid increase in temporary agency staff spending, which reached £3.3bn in 2014/15 and was on trend to grow by 30% in 2015/16.

A series of controls has been introduced starting last October with an overall ceiling placed on each provider’s agency nursing expenditure and a requirement to use only approved frameworks to source agency nurses.

However, the main control – a cap on the prices paid by providers to agencies – was brought in towards the end of November. These caps were initially set at a relatively high level around the median of what was being paid at the time. This equated to a 100% uplift on basic pay rates for nurses and 150% for junior doctors. Following a planned timetable, these were subsequently tightened to 75% and 100% in February and then 55% for both groups from April. Non-clinical staff caps were set at 55% from the outset.

The new capped rates are intended to be equivalent to national NHS pay rates for substantive staff, with the top-up covering holiday pay, employer national insurance and pension contributions, as well as the agency charge.

Levelling the field

The aim is that staff should see little or no benefit in pay rates for undertaking extra work through an agency rather than taking a full-time role or taking overtime or working through a trust’s own staff bank.

Additional controls setting out the maximum wage rates to be paid to agency workers – due to be introduced in July – will strengthen this further.

Chris Mullin, NHS Improvement economics director, says the organisation is happy with how the controls are working out. ‘It is in line with our best expectations and we are very pleased with the way the sector has got behind the initiative,’ he says.

Those expectations, set out in October, were to reduce spend by £1bn over three years. This figure was effectively made up of three years of estimated annual savings of £370m, across all three staff sets (medical, nursing, non-clinical) based on a compliance rate of 70%.

NHS Improvement says the service has already achieved savings of £290m from October to February. While this appears to put the service well on the way to meeting the overall annual saving, the sums are not completely comparable.

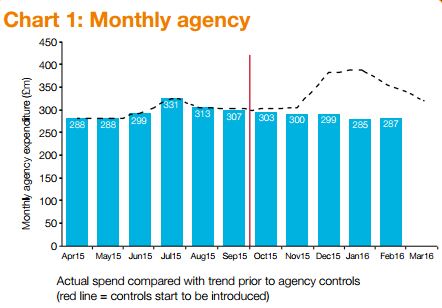

The £290m is based on the fact that the NHS spent £1.5bn on agency staff in the period. Based on previous trends (spending rose by 30% in the first six months of 2015/16 compared with the same period the year before), NHS Improvement says spending was expected to be in the region of £1.8bn.

So the nearly £300m of savings takes into account expected increases in agency costs, whereas the £1bn savings was compared with actual prior year expenditure. Neither of the savings figures takes account of any increased expenditure on substantive or bank staff as a result of any reduced agency usage.

The point is that agency spend is still growing if you look at quarterly spend compared with the same quarter the previous year – although the controls have put the brakes on the rate of increase – and month-on-month spend is falling (see charts).

Further, the February expenditure was a reduction of 13% compared with the peak monthly spend of £331m in July last year.

Mr Mullin adds that, in a March survey, two-thirds of providers said they had delivered net financial savings, with just 2% reporting increased net costs.

Reversal of growth

Formal reports also show a 5% reduction in agency spend for the quarter following the new rules’ introduction – from £951m in Q2 to £902m in Q3.

‘Prior to the new rules, spending was out of control,’ says Mr Mullin. ‘But we’ve seen a reversal of the growth trend, even though this has been in operation

during the winter months, when pressure on

staffing usually increases.’

He adds that providers also continue to back the new rules – both in general and the tightening of the ratchet with the lowering of the cap. ‘In our March survey, 71% said they supported the April ratchet, with just 16% saying no,’ he says.

‘We’ve also done some analysis on the prices, based on a sample of providers, and we’ve seen a 10% reduction in nursing prices between October and February,’ he adds. The overall thrust is that the policy is working.

Mr Mullin also wants to ensure that trusts look beyond the high-profile clinical roles involving doctors and nurses. Spend on agency staff actually splits fairly evenly between medical, other clinical and non-clinical staff – and savings are expected from all three areas.

Many of the high-volume breaches for trusts are in frontline roles with the cap breached by a small amount. But there are smaller numbers of breaches in administration and estates roles, with rates significantly above the capped levels.

‘Six months in from the introduction of the November rates and there are some very high prices being paid in these areas, with big potential savings,’ says Mr Mullin.

Not everyone is convinced the policy is fully working as intended yet. Financial and workforce solutions company Liaison has analysed data from a sample of 55 trusts that use one of its medical workforce systems. Just looking at four grades of doctors (consultants, staff grade, ST3 and FY2) in the first 10 weeks of the caps, it claims that 74% of shifts worked were not compliant with the rate caps. This was before the caps were made even lower and amounted to an overspend against the cap of £10.8m in 10 weeks across all trusts.

Also during April, Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust downgraded the emergency department at one of its hospitals to an urgent care centre. The trust blamed difficulties in recruiting middle grade doctors. While national shortages of emergency medicine doctors and too few doctors in training were issues, the trust said the national agency cap had also ‘impacted our ability to secure enough locums to fill gaps in the rota’. A February board paper had noted that ‘some organisations were offering advantageous pay rates to clinical staff outside the capped rates, which had attracted clinical staff away from the trust’.

NHS Improvement rejects any connection between the cap and the staffing problems at Lancashire, although it acknowledges there have been local pressures with significant jumps in demand. And it stresses that from the outset trusts have been able to override the caps if staff are needed to ensure patient safety.

However Mr Mullin says that the regulator would ‘come down hard’ on any trusts that were gaming the rules to attract staff. ‘We want trusts to work together and share data on compliance,’ he says.

It is not a straightforward issue. For a start, overrides do not necessarily represent non-compliance. And not all providers are required to adhere to the caps – foundation trusts not in breach of licence or in receipt of Department of Health financial support are ‘exempt’.

However, they are encouraged to do so and a value-for-money condition within the regulatory framework attempts to make it effectivel y a requirement.

y a requirement.

Mr Mullin (right) points out that ‘there is no foundation trust that isn’t attempting to comply with the caps’. This is further strengthened by providers’ access to sustainability and transformation funding being linked to compliance with the agency controls guidance. The exact nature of this compliance has yet to be confirmed, although it may well involve a trust not breaching its overall agency spending ceiling.

Despite a good start, Mr Mullin thinks the service can consolidate this improvement and do even better. ‘It’s a good news story from a finance perspective,’ he says. ‘However we don’t feel that finance directors are in the lead enough and if they were, I think we would be better placed to capitalise,’ he says.

Finance directors are the nominated lead for reducing agency spending in just ‘four or five’ out of around 240 trusts, according to NHS Improvement. Mr Mullin accepts some trusts may have done this deliberately to keep the emphasis on safe staffing rather than financial savings. But he thinks that trusts may be missing out on finance directors’ core skills.

‘This is bread and butter to finance,’ he says. ‘It is an opportunity to introduce good financial discipline across whole organisations – ensuring a more common approach across different areas. We have seen some organisations that have more of a grip on their agency nurse expenditure than with medical or with good finance systems in parts of an organisation. Finance directors may be better placed to ensure a more consistent approach and implement trust-wide systems.’

He also thinks that finance directors should be actively looking to take on this role. ‘Agency spend is a good leading indicator of the overall finances of a trust,’ says Mr Mullin. ‘A large chunk of providers’ costs is their workforce, and agency is close to being the marginal variation.’

The point is that if agency shift data provides the earliest indication of a potential overspend, finance directors should want

to be both getting the data as early as possible and proactive in implementing any mitigating measures.

NHS Improvement’s message is clear. It believes that finance director involvement equates to a stronger grip on agency spend and it wants to see more of them in the front line of this initiative.

Related content

The Institute’s annual costing conference provides the NHS with the latest developments and guidance in NHS costing.

The value masterclass shares examples of organisations and systems that have pursued a value-driven approach and the results they have achieved.