News / Hard times

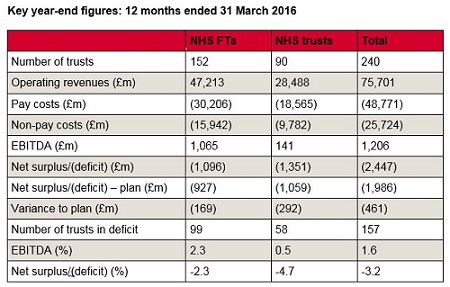

It is hard to put a positive spin on providers’ year-end financial figures, which showed a deficit of £2.45bn for 2015/16. NHS Improvement did flag up that things could have been worse – the run rate earlier in the year suggested a full-year deficit as high as £2.8bn. But in reality the ‘improved’ position masks a number of one-off measures, without which the problems would have been even more stark.

It is hard to put a positive spin on providers’ year-end financial figures, which showed a deficit of £2.45bn for 2015/16. NHS Improvement did flag up that things could have been worse – the run rate earlier in the year suggested a full-year deficit as high as £2.8bn. But in reality the ‘improved’ position masks a number of one-off measures, without which the problems would have been even more stark.

Providers may have been happy with the public tone of NHS Improvement’s announcement. It stressed that providers had ‘risen to the challenge of record-breaking demand’, seeing an ‘unprecedented 21 million emergency patients last year’ while making £2.9bn in efficiency savings.

At the end of May, it was still too early to say if providers’ improvement against mid-year projections had been enough to help the Department of Health stay within its global budget. But Jim Mackey (above), NHS Improvement’s chief executive, was determined to look for the positives.

‘When we consider where we were six months ago, NHS providers have done a great job in reducing the planned deficit,’ he said. ‘The key now is for us all to work together to make the necessary improvements in 2016/17, to reduce any variations in the quality of care for patients, and to bring the NHS provider sector back into financial balance.’

However, the figures make for undeniably difficult reading. Some 157 trusts reported a deficit, including 58 NHS trusts and 99 foundation trusts. Three quarters of these were acute bodies.

‘Distressing’ and ‘incredibly worrying’ was how HFMA director of policy Paul Briddock summed up the figures, confirming most people’s expectations. He also highlighted a survey by the King’s Fund released just ahead of the provider figures, which revealed finance directors were increasingly concerned about the impact of the financial situation on patient care.

‘With 65% of all providers and the majority of acute trusts wrapping up the year in deficit, the challenge for the coming year may push the NHS to its financial limit,’ he said.

Operationally, there are increasing signs that demand for services is outstripping funding. The 21 million accident and emergency attendances marked a 2.9% increase on the previous year. But in March, attendances were 7.5% higher than the same month in 2014/15.

Target pressures

The result has been that just 91% of A&E patients in aggregate were seen or admitted within four hours compared with the 95% target.

For Q4, this dipped to under 87% – the worst quarterly performance since the standard was introduced. There were also increases in four-hour-plus trolley waits, problems meeting ambulance response times and a failure to achieve the 92% referral to treatment target – again on the back of a 15% rise in the number of patients waiting to start treatment.

The £2.45bn deficit was almost three times greater than that reported in 2014/15 and £461m worse than the plan that providers started the year with, after they had been asked to revise plans. While the final figure is substantially north of the £1.8bn control total set for the service during the year, it has needed some £724m of ‘financial improvement opportunities’ to get even get this close. These ‘opportunities’ included £324m of local capital-to-revenue transfers and one-off technical measures.

NHS Improvement highlighted some of the key pressures driving the overspend. The cost of agency and contract staff was top of its list – as it has been for much of the year. Providers spent £1.4bn more than planned on agency staff, contributing to a £1bn overspend on their overall paybill after underspending on permanent and bank staff. There was not just a failure to deliver a year-on-year reduction in agency costs, but costs were in fact £545m higher than in 2014/15 – with nearly two-thirds of unplanned agency costs attributable to foundation trusts.

This increase in costs was despite mid-year introduced controls on agency spending – including overall spending ceilings, requirements to use procurement frameworks and rate caps. Despite the continued increases, NHS Improvement said the controls had had ‘some positive impact’. It has already estimated that the controls have saved £300m compared with what would have been spent (Healthcare Finance, May page 25) and £86m on management consultants. However, these figures take no account of any savings on permanent staff budgets where vacancies have required agency staff cover.

A report to NHS Improvement’s board at the end of May said that ‘over time we would expect a reduced level of reliance on agency staff as agency controls become further embedded, while providers put in place tighter financial controls, supported by more realistic workforce planning and more robust rostering practices.’

Elsewhere there have been claims that the NHS faces an uphill struggle in achieving compliance with new capped rates. Liaison provides systems to the NHS to help trusts manage temporary staffing. Its latest research on medical locums covering the second phase of rate caps introduced in February estimated that, based on a sample of 56 trusts, English trusts together overspent capped rates by an estimated £26.6m in just nine weeks.

‘While we are seeing increased conformance from trusts, particularly during unsocial hours, there is still a long way to go to improve the core rates, which account for 70% of locum hours,’ said Andrew Armitage, Liaison managing director. ‘Trusts are clearly struggling with negotiating lower rates of pay for certain types of locum.’

A report from the company said that trusts working together and collaborating with a common pool of agencies were having the most success in achieving the capped rates.

NHS Improvement also said that delayed transfers of care cost at least £145m – based on losing a reported 1.7 million bed days (11% more than in 2014/15). However, fully absorbed costs could be much higher – and this is unlikely to capture the real costs of delayed transfers, which Lord Carter highlighted as a ‘major problem’ facing the NHS.

Providers spent £143m on waiting list initiative work and outsourced £240m to other providers (including the independent sector). However, they still faced a total of £751m in finance and readmission penalties. Just £253m of this was reinvested directly with providers to improve operational flows, worsening provider’s cost pressures by a net £498m. In total non-pay expenses were £1.2bn over plan – a 4.8% overspend.

The £2.9bn of savings delivered through cost improvement programmes was £316m (9.8%) short of plan and £6m below providers’ forecast at Q3. More than 78% of the shortfall was due to under-delivery by acute providers. The £316m was made up of a gross shortfall of £403m on pay-related saving schemes and £87m over-performance on planned income generation schemes. Perhaps most worryingly, just 78% of CIPs were achieved from recurrent schemes, well below the planned level of 92%.

Providers’ combined deficit exceeds the sustainability and transformation fund that was set at £1.8bn (equivalent to the 2015/16 control total that had been set for providers). Given this was intended to support providers in returning to financial balance, providers will need to deliver higher levels of efficiency in 2016/17 to achieve their set and agreed control totals.

In contrast to their revenue performance, providers’ cash position showed continuing month-on-month improvements. The closing cash position of £4.2bn at month 12 was £615m better than plan, reflecting constraint on capital expenditure and management of working capital.

Capital expenditure of £3.7bn was £1.4bn below plan – an underspend that was in line with historic patterns. The underspend also included the £324m transferred to revenue budgets.

NHS Improvement warned that, with capital ‘highly constrained’ from 2016/17, providers should ‘procure their capital assets more efficiently, consider alternative methods of securing assets, maximise disposal proceeds and extend asset lives’.

King’s Fund director of policy Richard Murray said there needed to be recognition of the cause of the financial problems. ‘Overspending on this scale is not down to mismanagement or inefficiency in individual trusts,’ he said. ‘It shows a health system buckling under huge financial and operational pressures.’

He added that trusts starting the year with a collective deficit of about £1bn more than planned had ‘worrying implications’.

NHS Providers chief executive Chris Hopson put it bluntly. ‘This record number of trusts in deficit, with a record overall deficit, is simply not sustainable. We have to rapidly regain control of NHS finances otherwise we risk lengthening waiting times for patients, limiting their access to services, and other reductions in the quality of patient care.’

Following the publication of Lord Carter’s report, productivity improvements have been the prime focus. But funding appears to be moving back to the centre stage.

‘By 2020 public spending on the NHS is set to drop further to below 7%. This is simply not enough and we need to stop pretending it will be,’ added Mr Hopson.

‘There is now a clear gap between the quality of health service we all want the NHS to provide and the funding available. What we can’t keep doing is passing that gap to NHS trusts – asking them to deliver the impossible and chastising them when they fall short.’

Related content

The Institute’s annual costing conference provides the NHS with the latest developments and guidance in NHS costing.

The value masterclass shares examples of organisations and systems that have pursued a value-driven approach and the results they have achieved.