Feature / The demand puzzle

Activity is rising and steps to curb it are an important element of sustainability and transformation plans. But what is fuelling demand and how is the NHS trying to reduce the pressure? Seamus Ward reports

There is growing concern about the rising demand for NHS services. Activity and waiting lists are on the up and the NHS may not be able to live within its means if it is not controlled. Of course, the health service has many demand management initiatives, which in many cases report impressive results, but so far at least they have not been able to quell the rising tide of need.

Given the financial climate, it is not surprising that demand management is a major part of the £22bn of savings set out in the Five-year forward view and each sustainability and transformation plan must include a section on addressing demand. However, to address demand it must first be understood.

While demand is not a modern phenomenon in the NHS, the issue came into sharp focus in the last few months. Traditionally, the summer months offer trust A&E departments in England a respite after the high-demand winter. But official figures show that this winter effect is happening all-year round.

This summer’s A&E waiting time performance was worse than every winter for the past 12 years bar one. Between June and August, 90.6% of patients were seen in four hours – worse than every winter since 2004 except last winter, when the figure was 89.1%.

In August, NHS Improvement published promising first quarter financial figures for English providers – with a deficit of £461m – £5m better than planned.

While this was positive news, it warned that activity continued to rise, with an extra 300,000 A&E attendances compared with the same quarter in 2015/16 and a 6% rise in emergency admissions.

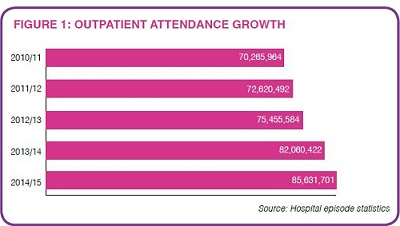

Figures for August see the upward trend continuing with A&E attendances up 4.2% and emergency admissions up 3.8% on the previous year. Outpatient attendances are also increasing (see figure 1). Elective care is also on the rise, with consultant-led treatment 4% higher and diagnostic tests up 5.5%.

David Maguire, economic and data analyst at the King’s Fund, says demand has been rising for years across all clinical areas and sectors, creating something of a perfect storm for the NHS to face.

‘If you look at activity rates, they have got higher and higher over the past 10 years. Activity in outpatients, elective, non-elective and A&E attendances are all going up.’

He adds that demand is increasing in primary care too, demonstrated in the King’s Fund report Understanding pressures in general practice, published earlier this year. The study found a 15% increase in GP consultations between 2010/11 and 2014/15, with face-to-face consultations rising by 13% and phone consultations by 63%.

‘It shows not only more contacts with GPs, but also the patients had a higher average age and that people were presenting with a greater average number of comorbidities. The geing population is certainly a factor,’ Mr Maguire says.

Around 15 million people in England have a long-term condition and, while the number with one long-term condition is forecast to remain relatively stable over the next 10 years, those with multiple conditions is set to increase to 2.9 million in 2018 – one million more than in 2008.

The likelihood of long-term conditions rises with age and by 2034 the number of over-85s is set to reach 3.5 million (5% of the population) – 2.5 times more than in 2009. The King’s Fund report said the average number of chronic conditions was 3.27 in patients over 85.

Avoidable problems that lead to hospital admissions are on the rise. For example, malnutrition as a primary diagnosis for admission rose from 544 patients in the period August 2010–July 2011 to 730 in August 2014 – July 2015. Half of the patients admitted in the latter period were over-60.

This ageing population and pressure on primary and social care is having an impact on secondary providers. The latest NHS England statistics show the number of people admitted from A&E is up from 19% of attendances in 2002/03 to 27% last year.

According to Mr Maguire, either people are presenting at A&E in a worse state or clinicians are getting more cautious.

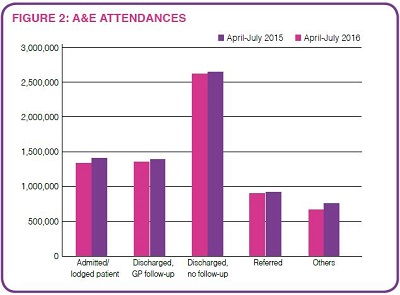

Looking at the latest HES data, there was a 3.8% rise in A&E attendances between April and July compared with the same period in 2015. However, there appears to be some opportunity to reduce A&E attendances (figure 2). The biggest proportion of patients (37%) was discharged with no further need for treatment or advice.

And, while just under a fifth were admitted, a similar proportion were discharged to the care of their GP. This does not mean these groups of patients were wrong to go to A&E in the first instance, but some experts believe it shows patients need better signposting through the system.

It can be difficult to discharge some medically fit inpatients safely, particularly the elderly, with hospitals waiting for care packages to be arranged in the community. These delayed transfers of care are rising and were identified as a threat to NHS efficiency in the Carter report. The latest figures show 188,300 delayed days in August 2016, of which 127,500 were in acute care. A year earlier there were 145,100 delayed days, of which 93,100 were in acute settings – total delayed days in acute care rose by 37% in the last year.

However, NHS England said 59% of the delays in the latest figures were due to the NHS, 33% caused by social care and around 8% due to both the NHS and social care.

According to Mr Maguire, the funding gap in social care is likely to be at least £2.8bn by 2019 and, combined with the rise in delayed discharge, the pressure on acute providers could only get worse.

Diverting patients away from hospital to care in a more appropriate setting is a key pillar of demand management initiatives. But they encompass a range of actions.

Longer term, it can mean promoting healthier lifestyles now, so people can avoid chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and cancers when they get older. This will, of course, do little to address the pressures immediately at hand.

Self-care options

Shorter term, demand management can mean closely monitoring the health of people with chronic illnesses to intervene early before their condition worsens and they require a hospital admission. This can be performed by a clinician, remotely or face to face, or, in the case of self-care, by the individual themselves.

Self-care opens up the possibility of apps that measure or remind the patient to measure vital statistics – blood glucose, heart trace or blood pressure, for example. Its potential to cut costs while improving the patient experience – by making them feel more involved in their care – is generating much excitement among healthcare providers and funders across the developed world.

Linked to this, demand management can mean moving care out of hospital to the community, with care services provided by specialist GPs and nurses, or even peripatetic ‘hospital’ doctors.

NHS England also believes giving patients full choice in their treatment – whether to self-care, defer treatment or, where the 18-week standard is likely to be breached, an option to choose an alternative provider – is important in demand management. It believes choice can spread demand across the system – patients who prioritise waiting times will choose providers with shorter waits, for example.

Demand management can also mean tougher referral thresholds or rationing. This year, several clinical commissioning groups have been criticised for plans to limit some types of surgery, including preventing patients with a high body mass index from having hip and knee replacements, for example.

Some CCGs have introduced referral management systems (see box) to ensure patients are seen in the most appropriate setting. The operational planning guidance for 2017/18 and 2018/19 outlines a number of demand reduction measures, including implementing RightCare elective care redesign and urgent and emergency care reform.

Of course, moving care to another setting merely deflects demand to another part of the healthcare system. This has led to warnings that moving care out of hospital and into the community may not reduce overall costs.

Last month, Katherine Checkland, professor of health policy and primary care at University of Manchester, told the Lords inquiry into NHS sustainability that expectations of demand management were too high. ‘Part of the problem is that a lot of the expectations of demand management are overblown. There is the idea that by prevention you will save a lot of money or that doing things out of hospital will be a lot cheaper. The problem is expectations have been too high,’ she said.

RightCare way

She added that savings could be found in examining the value of clinical interventions and driving out unwarranted variations, particularly through schemes such as RightCare. RightCare works with local health economies to identify variation in geographically similar populations; shift the conversation to population healthcare rather than individual organisations; identify the best opportunities to improve the population’s health; and use evidence-based processes to make sustainable change to care pathways and reduce unwarranted variation.

It is working with 65 local health economies and 144 more are to join the programme in December. National director Matthew Cripps says the initiative is well placed to understand the relationship between demand and value.

‘Every local health economy involved in wave one of the RightCare programme has identified three to four pathways that offer the largest opportunity for change, using RightCare data as their starting point for understanding opportunities. As the data compares each local health economy to similar populations, demand issues for priority programmes are flushed out early,’ he says.

‘Local health economies involved in piloting and early implementation of the RightCare approach provide good examples of how powerful the programme can be in addressing two aspects of demand management – both making sure the patients reach the right setting and prevention being utilised effectively to reduce overall demand.’

Professor Cripps gives two examples of how the RightCare approach is aiding demand management. Using RightCare principles – where to look, what to change, how to change – two clinical commissioning groups, Ashford CCG and Canterbury and Coastal CCG, identified the need for a triage service for musculoskeletal referrals. Triage was introduced in December 2014 and in the first 12 months referrals fell by 30%, producing an annual saving of £1m. With fewer referrals, waiting times have improved and the detailed comparative analysis of referrals and interventions has prompted plans for a new integrated model for local orthopaedic services.

Bradford Districts CCG is using RightCare to tackle cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of death locally. It aims to reduce cardiovascular events by 10% by 2020 – including 150 strokes and 340 heart attacks over the period.

Taking the population approach of RightCare, it has identified 7,000 patients with a more than 10% risk of stroke and given them statins to reduce their cholesterol levels. A further 6,000 already taking statins have been prescribed a more effective form of the drug. Almost 1,000 people with abnormal heart rhythm have been given blood thinners to cut their risk of stroke, while 38,000 have joined a new programme to monitor and control their blood pressure.

The nature of rising demand is complex and the response to it equally so. True reduction in demand can only come in the long term – the outcome of successful public health programmes. But until this happens, demand management will mean deflecting care away from hospitals to more appropriate parts of the system, which face their own demand challenges.

Referral cuts

North Tyneside Clinical Commissioning Group has seen significant reductions in referrals to secondary care. Commissioning and performance manager James Martin says this is in part due a new referral management service.

‘One of the big drivers is to reduce variation between practices in terms of referrals and to standardise the way things are done,’ he says. ‘There can be differences in GPs’ clinical knowledge and how comfortable they are about making decisions.

‘GPs refer patients through the e-referral system, with their cases reviewed by consultants. There are several outcomes to the review – the patient is listed for an outpatient appointment; the patient is referred back to primary care with a care plan; or the consultant requests further information.

In the latter scenario, the GP may not have carried out steps outlined in the referral protocol, such as diagnostic tests.

Mr Martin accepts referrals back into the community and managing patients through the process has meant extra work for GPs, but he adds: ‘The patient needs to be seen somewhere – this is about ensuring they are seen in the right setting.’

Initially the focus was on the specialties with the biggest volume of referrals – orthopaedics, ophthalmology, ENT, dermatology and gynaecology – before being rolled out to others. ‘We have also had two facilitators work with the practices with the biggest level of variation to make changes that will reduce that variation.’

The work, along with the CCG QIPP scheme, meant that in May, across all referrals, numbers were down by about 10% compared with 12 months earlier. Or, looking only at GP referrals, they were down 13.4%.

Related content

The Institute’s annual costing conference provides the NHS with the latest developments and guidance in NHS costing.

The value masterclass shares examples of organisations and systems that have pursued a value-driven approach and the results they have achieved.