Covid-19 reader: 4 February

Lockdown; did the benefits outweigh the costs

Johns Hopkins Institute, research

Lockdowns have had little to no effect on Covid-19 mortality. This was the rather dramatic finding of research led by The Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics. It went on to conclude that lockdown policies are ‘ill-founded and should be rejected as a pandemic policy instrument’.

Lockdowns have had little to no effect on Covid-19 mortality. This was the rather dramatic finding of research led by The Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics. It went on to conclude that lockdown policies are ‘ill-founded and should be rejected as a pandemic policy instrument’.

The study, which also involved researchers from Sweden’s Lund University and Denmark’s Centre for Political Studies, involved a meta-analysis of different investigations into lockdown measures. (Lockdown was defined as the imposition of at least one compulsory, non-pharmaceutical intervention (NPI) such as limiting internal movement, closing schools and businesses, and banning international travel.)

NPIs were first implemented in China at the onset of the pandemic. This was soon followed by Italy and then by virtually all other countries. According to the research report, early epidemiological studies predicted large effects of NPIs, with one simulation suggesting Covid mortality could be reduced by up to 98%.

While there were studies that found impacts both ways, the overall conclusion of the analysis was that it failed to confirm a large significant effect on mortality rates. It said studies examining the relationship between lockdown strictness and deaths found that the average lockdown reduced Covid-19 mortality by 0.2% compared to a Covid-19 policy based solely on recommendations. Shelter-in-place orders were also ineffective – reducing mortality by 2.9%. And there was no broad-based evidence in support of specific NPIs (such as facemask or closing schools), although closing non-essential businesses such as bars seemed to have some effect (reducing mortality by 11%).

In contrast, ‘lockdowns during the initial phase of the Covid-19 pandemic have had devastating effects,’ the study said. It listed: reducing economic activity, raising unemployment, reducing schooling, causing political unrest, contributing to domestic violence, and undermining liberal democracy.

The researchers acknowledge studies that both support and contradict their findings and suggest four reasons for why their assessment may be correct. First, people respond to dangers outside their door – people will socially distance during a pandemic regardless of what governments mandate. Second, mandates only regulate a fraction of potentially contagious contacts – they cannot enforce handwashing, coughing etiquette or distancing in supermarkets for example.

Third, even if lockdowns are successful initially, people may respond to the lower risk by changing behaviour. And fourth, unintended consequences may play a larger role than recognised. Isolation of an infected person at home could risk infecting family members with a higher viral load. And lockdowns may limit access to safe outdoor spaces, pushing people to meet at less safe indoor places.

It further explains differences between countries by differences in population age and health, as well as other factors such as culture, communication and coincidence. It concludes that the costs to society must be compared to the benefits of lockdowns, which it claims are marginal at best.

Pandemic update: two years and counting

World Health Organization, speech

It has been two years since the World Health Organization declared a public health emergency of international concern – its highest level of alarm – over the spread of Covid-19.

At that point, there were fewer than 100 cases and no deaths reported outside China. But how things have changed. Two years on, more than 370 million cases have been reported and more than 5.6 million deaths – figures that are widely believed to be an underestimate of the real tally for the virus.

Underlining the point that the pandemic has not ended, WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus (pictured), this week said that Omicron had contributed 90 million cases to the overall number in just 10 weeks – more than the total cases reported in 2020.

‘We are now starting to see a very worrying increase in deaths in most regions of the world,’ he said. ‘We’re concerned that a narrative has taken hold in some countries that because of vaccines, and because of Omicron’s high transmissibility and lower severity, preventing transmission is no longer possible and no longer necessary. Nothing could be further from the truth.’

More transmission would mean more deaths. And, while the world health leader was not calling for a return to lockdown, he urged countries to use ‘every tool in the toolkit, not vaccines alone’.

‘It’s premature for any country either to surrender or to declare victory,’ said Dr Tedros. The virus was continuing to evolve with four Omicron sub-variants currently being tracked. He called for countries to continue testing, surveillance and sequencing.

To combat the evolving virus, vaccines may also need to change. He said preparation should start now to reduce the time required for large scale vaccine manufacture later.

Recognising the importance of reinfections

UK Health Security Agency, announcement

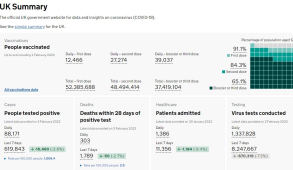

Observant Covid-19 dashboard watchers may have noticed a sudden increase in infections earlier this week. While Omicron has been doing its best to inflate case numbers all on its own, this particular overnight hike actually reflects a change in the way cases are reported.

From Monday (31 January), cases involving a reinfection are now included in the daily and cumulative count. Previously people testing positive for Covid were only counted once in case numbers. A repeat positive test – no matter how long the duration between infections – was simply not counted.

However, new rules now apply. Positive tests within 90-days of a previous positive test are still not counted. They continue to be treated as part of the same case episode. But positive tests outside those parameters are now included as reinfection episodes.

The updated figures for 31 January for England, show 14.8 million cases since the start of the pandemic – a more than 800,000 increase on the previous day’s cumulative total. However, the new total includes some 588,000 reinfections. With just under 82,000 ‘new’ cases reported the same day – a figure that will itself include some reinfections – this doesn’t quite explain the difference between the two days running totals.

The gap is made up by the addition of a further 175,000 cases that have been added to the pot. This is the result of a new algorithm used to check existing surveillance data, which has identified extra cases that were previously removed as duplicates.

Reinfection rates averaged about 1.4% of cases until the middle of November. At this point there was a spike in infections following the emergence of the Omicron variant. Reinfections now represent around 10% of episodes per day. And since the start of the pandemic, reinfections account for some 4% of total infections.

Reinfection data is now being reported within and alongside infection totals for England and Northern Ireland. Changes are also being introduced in Scotland and Wales.

‘Reinfection remained at very low levels until the start of the Omicron wave,’ said Steven Riley, UK Health Security Agency director general of data and analytics. ‘It is right that our daily reporting processes reflect how the virus has changed. We continue to see downward trends in case numbers and incidence of illness as we work to reduce the impact of the pandemic on our day-to-day lives.’

Related content

The Institute’s annual costing conference provides the NHS with the latest developments and guidance in NHS costing.

The value masterclass shares examples of organisations and systems that have pursued a value-driven approach and the results they have achieved.