Covid-19 reader: 11 February

Government justifies U-turn on staff vaccination

Department of Health and Social Care, consultation paper

Having announced a major change of mind on mandatory vaccination of health and care staff at the end of January, the government has been quick to consult on its plans to revoke changes to the very recently amended legislation. The new regulations were already in place for care home staff and were due to go live for health and wider social care staff from April.

Having announced a major change of mind on mandatory vaccination of health and care staff at the end of January, the government has been quick to consult on its plans to revoke changes to the very recently amended legislation. The new regulations were already in place for care home staff and were due to go live for health and wider social care staff from April.

There had been increasing concerns about the numbers of staff who would remain unvaccinated by the April deadline. Because of the time required between vaccines, the timetable had meant that unvaccinated staff would have needed to receive a first dose of vaccine by 3 February to enable completion of the whole course by the deadline. Those choosing to remain unvaccinated faced redeployment, where possible, or dismissal. And this would come at a time when the NHS and care services already face major staffing challenges, both as result of long-standing vacancies and because of Covid-related isolation.

It is the exacerbation of these staff shortages that is widely believed to be behind the government’s U-turn. However, its new consultation insists the revised position is based on an updated clinical rationale, and related to the reduced severity and lower virulence of the now dominant Omicron variant, which was yet to emerge when the original regulations were laid.

The risk of presentation to emergency care or hospital admission is approximately half of that for the previously dominant Delta variant. And coupled with the high vaccination rate in the population, this has meant the circulation of Omicron has been less than feared.

The government also pointed to continuing strong infection control measures in place across health and social care and the fact that the NHS continues to have access to regular testing. Its conclusion was that ‘it is no longer proportionate to require vaccination as a condition of deployment through statute in health, care homes or other social care settings’.

The government’s original impact assessment of the mandatory vaccination policy suggested that around 88,000 health and 35,000 domiciliary care staff may have chosen to leave their jobs rather than have a vaccination. This included 73,000 workers in the NHS and the cost of replacing these staff could have been £153m.

However, the short-lived policy of mandatory vaccination has had some impact. The government said that there had been a net increase of 134,000 people working in NHS trusts who had received a first dose of vaccine since it originally consulted on its vaccination proposals. Nineteen out of 20 NHS workers have now received a first dose, it said. During the same time, some 36,000 more people working in social care also came forward for vaccination.

Funding call to address global Covid inequity

World Health Organization, announcement

The World Health Organization this week called on rich countries to find $16bn to fund its Access to Covid-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator programme to help end the pandemic as a global emergency in 2022.

The programme aims to provide low- and middle-income countries with access to Covid tests, treatments, vaccines and personal protective equipment. The total funding needed is $23bn with $6.5bn to be self-financed by middle-income countries, supported by multilateral development banks.

A finance framework has been developed setting out fair share contributions for each country based on the size of their economy and what they would gain from a faster global recovery.

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO director-general, said that in some parts of the world, it might feel like the pandemic is almost over, while elsewhere it was at its worst. ‘But wherever you live, Covid isn’t finished with us,’ he said, adding that Omicron had demonstrated that any feeling of safety could change in a moment.

The virus would continue to evolve, but the world was not defenceless and had tools to prevent the disease, test for it and treat it. ‘Where people have access to those tools, this virus can be brought under control,’ said Dr Tedros. ‘Where they don’t, this virus continues to spread, to evolve, and to kill.’ The ACT Accelerator aims to ensure all countries have access to these tools.

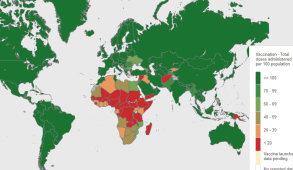

While 4.7 billion tests have been administered since the start of the pandemic, only 22 million have been delivered in low-income countries. And only 10% of people in low-income countries have received at least one vaccine dose – a global position visibly demonstrated by the WHO’s Covid map (pictured).

The $16bn of funding would support the target of 70% vaccine coverage in all countries by mid-2022, creating a pandemic vaccine pool of 600 million doses. It would also buy 700 million tests, expand sequencing capacity and buy treatments for 120 million patients, as well as 433 million cubic metres of oxygen.

The WHO has been consistent with its message that the massive global inequity in the ability to respond to Covid not only hurts poorer countries, but risks the emergence of new, more dangerous variants, which has implications for even highly vaccinated populations.

Dr Tedros admitted the funds needed were significant. ‘But [they are] less than the monthly economic costs of the pandemic,’ he said. ‘We have a plan. We have the tools. We have hope. Now we need the resources to execute the plan everywhere, make the tools available everywhere, and make hope a reality everywhere.’

Looking for evidence to support the removal of restrictions

Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies, minutes

Prime minister Boris Johnson this week announced that all remaining Covid restrictions – including the requirement for those who test positive to self-isolate – could end later this month. The restrictions were not due to expire until 24 March. The news met with a mixed response with some welcoming the move, while others saw it as an attempt to distract attention from the Conservative leader’s current ‘partygate’ difficulties.

Representatives of the hospitality sector said the proposed changes would be a welcome relief, helping the sector to recover. However, one scientist described the proposals as either ‘very brave or very stupid’.

There are certainly encouraging signs in the government’s Covid-19 dashboard. The seven-day average case numbers continue to fall – with the 66,638 cases reported on Thursday representing a 25% reduction compared with a week earlier. And the number of hospitalisations – currently around 1,300 a day – also continues to decline albeit slowly and steadily.

However, arguments about protecting the NHS – one of the main stays of the case for restrictions in the first place – still appear valid. The NHS Confederation urged caution this week. ‘With over 11,400 people in hospitals across the country right now with the disease and, on top of that, around 1.3 million people believed to have long Covid, leaders remain very aware that the virus is still here and that it will continue to present challenges to the NHS,’ said the representative body’s chief executive Matthew Taylor (pictured).

‘Around 40% of NHS staff absences are due to Covid currently and so removing the self-isolation requirements could bolster capacity significantly at a time when the service is committed to tackling its waiting lists,’ he added. ‘But we have to be mindful that it could also lead to higher rates of transmission, which could then lead to more admissions into hospital alongside more ill health in the community.’

He called for transparency about what the scientific advice says about self-isolation and for a cautious approach with a readiness to review the decision if new threats emerge. Minutes from the latest Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) meeting, at the end of January, suggest that an early end to the restrictions was not discussed.

The minutes acknowledge that hospital admissions and bed occupancy levels are decreasing. However, the long-term pattern of the epidemic in the UK is ‘highly uncertain’, and future waves of infection should be expected. ‘The number, timing and characteristics of future variants is very unpredictable and future waves could still result in high numbers of infections, admissions and deaths,’ the committee said. ‘One possible scenario is the co-circulation of multiple variants with different characteristics that primarily impact different groups of the population due to heterogeneity of immunity and behaviour.’

It added that, in the long run, most waves were likely to occur in the autumn/winter, although non-seasonal waves could be a feature in the short to medium term due to the emergence of new variants or waning immunity.

Related content

The Institute’s annual costing conference provides the NHS with the latest developments and guidance in NHS costing.

The value masterclass shares examples of organisations and systems that have pursued a value-driven approach and the results they have achieved.